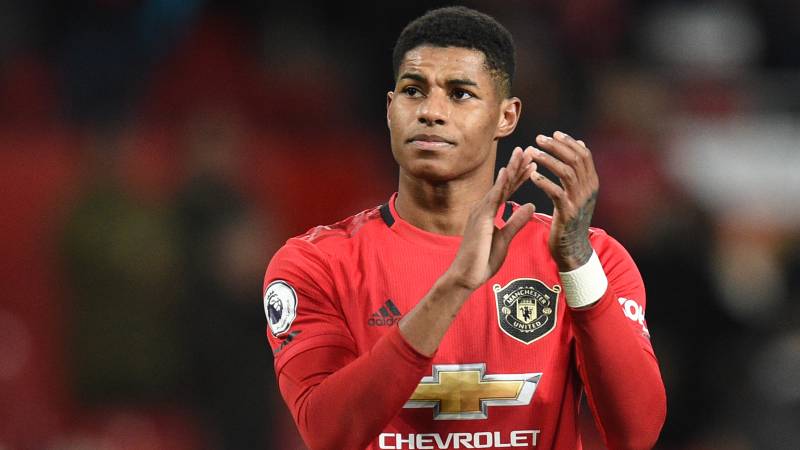

Rashford 1 UK govt 0: footballer forces change on child poverty

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

The British government on Tuesday bowed to demands by Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford to change its policy on free school meals for the poorest children, amid growing concerns about the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on low-income families.

The England international drew on his own experience of growing up in poverty to lead an impassioned campaign for the programme to be extended through the summer holidays. Prime Minister Boris Johnson's government had initially resisted making the change, which would see 1.3 million children in England receive vouchers for an extra six weeks.

But as the story dominated the headlines and opposition MPs and members of his own Conservative party came out behind Rashford, he gave in.

"Owing to the coronavirus pandemic, the prime minister fully understands that children and parents face an entirely unprecedented situation over the summer," his spokesman said. "To reflect this we will be providing a Covid summer food fund. This will provide food vouchers covering the six-week holiday period."

Rashford, 22, responded on Twitter: "I don't even know what to say. Just look at what we can do when we come together. THIS is England in 2020."

The striker had written to Johnson and MPs and on Tuesday wrote in The Times newspaper that he understood personally how much free school meals mattered to children receiving them. "Ten years ago, I was one of them. I know what it feels like to be hungry," he wrote. "I'm well aware that at times my friends only invited me to eat at their houses for their parents' reassurance that I was eating that evening."

Ahead of a parliamentary debate called by the main opposition Labour party, Rashford urged MPs to put aside their political differences and back his campaign. Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon also announced Tuesday that she would extend the meals scheme to the summer holidays in Scotland, following a move already made by the devolved government in Wales.

Educational poverty

Johnson had highlighted how much his government has already done to help people hit by nationwide stay-at-home orders imposed in March to stem the spread of COVID-19. When schools were shut, pupils eligible for free meals were offered vouchers instead, and the government has boosted welfare payments and provided targeted funds for the most vulnerable.

It has also paid the salaries of 9.1 million people in its furlough scheme as of June 14, although new figures show a surge in claims for out-of-work benefits to 2.8 million people in the three months to May.

But fears are growing for how many people will cope when the furlough scheme ends in October, with a deep recession looming. Several Conservative MPs had called on Johnson to "do the right thing" and extend the school meal programme.

Commentators also questioned why the prime minister was picking such a fight when he was already on the back foot over his response to the coronavirus outbreak, which has seen more than 41,000 deaths.

"MarcusRashford is right. Public know it. Politicians know it," tweeted Conservative MP Robert Halfon, the chairman of the Commons education committee. "He's lived food hunger and helps food charities," he said, referring to Rashford's help in raising £20 million ($25 million) for FareShare, a charity that fights hunger and food waste.

Labour's education spokeswoman, Rebecca Long Bailey, said earlier that Rashford was "one of the best of us", accusing the government of being "callous". Welfare minister Therese Coffey drew criticism online for her initial response to Rashford's article, which was to refute a claim he made that families might have their water cut off if they could not pay. She later put out a series of tweets saying that she and Rashford "are working to the same aim".

Halfon has previously warned about "an epidemic of educational poverty" after the government conceded most children would not return to school until September. A new study from UCL's Institute for Education found just 19 percent of children were spending more than four hours a day on school work, falling to 11 percent for those on free school meals.