China seeks to boost Shanghai bloc to counter the West

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

China is seeking to strengthen its leadership of an expanding bloc of nations it sees as a potential counterweight to the world order led by the United States.

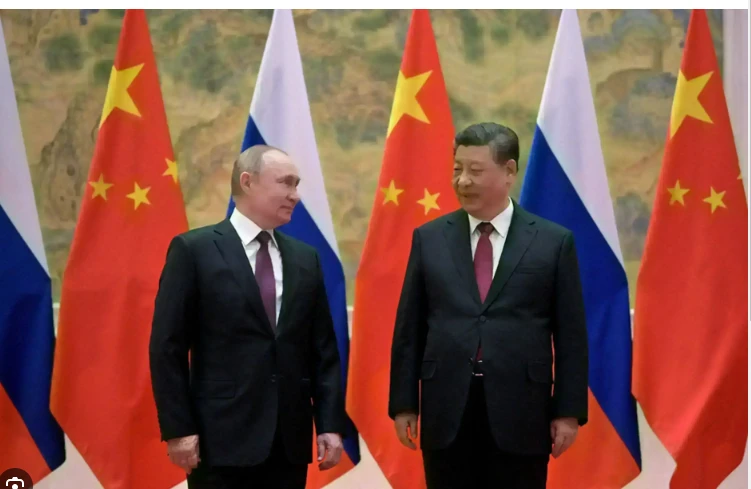

Leaders of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) member states met last week in Kazakhstan, with President Xi Jinping calling on strategic ally Russia and other partners to "firmly support each other".

Founded in 2001 by Beijing and Moscow as an economic and security grouping, it includes India, Pakistan and several Central Asian states.

It expanded last year to include Iran and this year welcomed Belarus.

The talks in Astana took place ahead of this week's NATO summit in Washington, where the Western military alliance is marking its 75th anniversary and reaffirming its support for Ukraine.

In stark contrast, the SCO's joint declaration made no mention of Russia's war in Ukraine, or of Taiwan, which China claims as part of its territory.

With China assuming the annual rotating chair of the SCO, analysts expect it will work to integrate the two new members and boost collaboration across its vast remit -- bolstering, in turn, its own leadership of the alliance.

"The SCO is increasingly defining itself as an alternative vision for world order, juxtaposed against the traditional postwar order led by the United States and other Western powers," said Bates Gill, a senior fellow for Asian security at the US-based National Bureau of Asian Research.

The bloc's expansion to include new members could be seen as echoing Xi and Putin's repeated calls for their vast region to resist Western influence.

The SCO claims to represent 40 percent of the world's population and about 30 percent of its GDP, but its members have diverse political systems and even open disagreements with one another.

Zhang Xiaotong, director of the China and Central Asia Studies Center at Kazakhstan's KIMEP University, said Beijing would look to boost trade among members as it grapples with efforts to contain its growing influence in Asia, and an economic slowdown at home.

"China is likely to... encourage peace in the Eurasian continent and put economics at the centre of SCO agenda so as to help improve (its) growth," he told AFP.

- 'Alternative vision' -

China and Russia have historically used the SCO to deepen their own ties with Central Asian states and vie for influence in the region.

Recently, however, they have increasingly pitched the organisation as a competitor to the West.

Last week's SCO declaration blasted the "unilateral and unrestricted build-up" of missile defence systems in what appeared to be a thinly veiled swipe at Washington.

Xi also said the group should "resist external interference" and "firmly support each other", while Putin hailed the arrival of a "multipolar world".

"China will try to use the next 12 months to... find common ground among all 10 member states," said Eva Seiwert, an analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a Berlin-based research institute.

Abanti Bhattacharya, a professor of East Asian Studies at India's University of Delhi, said China had given the SCO "greater traction" especially since its flagship Belt and Road infrastructure initiative (BRI) had begun to attract criticism.

Beijing argues the BRI has brought mutually beneficial development to partner countries, but critics say it has saddled poorer nations with debt.

"It simply boils down to one reality: (the) return of the Cold War (as) the world is getting divided into two blocs, democratic and authoritarian," Bhattacharya told AFP.

- 'Pompous rhetoric' -

Other analysts were sceptical that the SCO could pose a direct challenge to the West, pointing to longstanding frictions between member states.

"The bloc seems to see itself as a way to help its members withstand pressure from the United States and its allies in Europe and Asia. That said, not all SCO members seem to be on the same page," said Ja-Ian Chong, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore.

With China competing for influence with Russia, and with India over territory, it remains unclear if the forum can fulfil its grand ambitions.

Temur Umarov, a fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, said the SCO was "ineffective and overblown", lacked a "uniting goal" and failed to assign serious responsibilities to members.

Behind the "pompous and impressive rhetoric", he said, it "doesn't really have any power to make change... inside or outside the SCO's borders".