Canada's Quebec province expands assisted dying

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

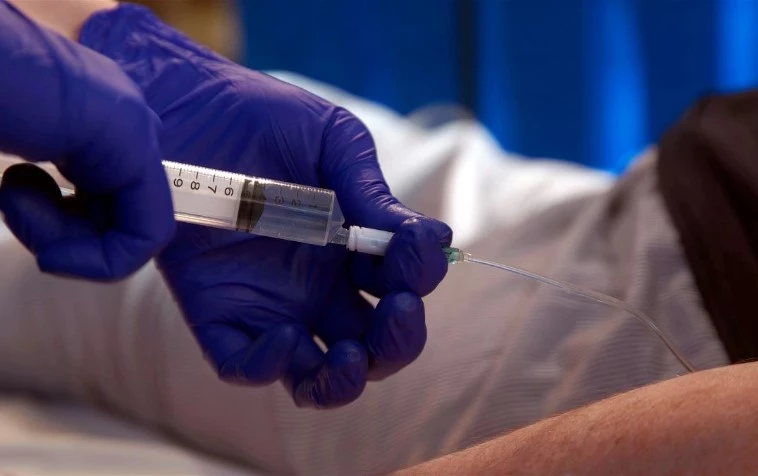

Colette Julien, like thousands of sick Canadian compatriots each year who seek an end to their suffering and dignity in death, requested medical assistance in dying -- a regime that Quebec province this month moved to expand so as to cover more ailments.

By the end of the year, approximately eight percent of all deaths in the province will have been the result of doctors' help, according to government projections.

Since introducing the option in 2015, the number of assisted deaths in the province has outpaced the rest of Canada (3.3 percent), as well as the Netherlands (4.8 percent) and Belgium (2.3 percent) which have older euthanasia laws.

"I've reached the end of the road and am not interested in trying to extend my life a couple of months," Julien told AFP a few days before being pricked with a fatal injection.

"I just want to be at peace," said the diminutive 77-year-old. It was a carefully considered decision, she said, that was partly motivated by fears of losing her autonomy and freedom.

"When you're sick, you have to depend on others. Me, depend on others excessively? No, no, no, no," said the retired nurse, who was diagnosed with lung cancer that spread to her brain.

Nancy Carpentier, Julien's niece who helped care for her when her health began to fail, expressed strong support for her final wish to avoid the kind of suffering that Carpentier's father went through in his last days.

A doctor-assisted death, she said, is "a beautiful undertaking." It allowed Carpentier to spend "quality time" with her aunt, have long chats and share "a moment of reflection" with her, she said, adding that she hopes to have the courage to seek an assisted death should she herself fall badly ill one day.

- 'Last resort treatment' -

In 2022, 4,810 people received medical assistance in dying, or MAID, in Quebec.

On June 7 the regime was expanded to allow persons suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's, to request it in advance -- before their mental competence degrades.

The amended law will also require palliative care homes and private hospitals to offer access to MAID. And nurses will be authorized to administer it in the same way as doctors.

"Medical assistance in dying is considered a last resort treatment," Sonia Belanger, Quebec's minister for health and seniors, told AFP.

Almost 90 percent of people who received MAID had cancer, neurodegenerative or neurological diseases, or respiratory or cardiac ailments. And the vast majority were in an advanced or terminal phase of their sickness.

"You have to be careful," said Belanger. The aim of the extension of the MAID law is not to increase the number of assisted deaths. "Not at all. It is really a question of meeting the needs of people who want it," Belanger added.

Despite broad support for MAID, its expansion worries some. It is a "disappointment" for the Group of Activists for Inclusion in Quebec (RAPLIQ), which defends people with disabilities from discrimination. They were also made eligible for MAID by the legal changes.

"Not only is it permissive, it's dangerous. It's almost encouraging people who are exhausted to die," laments RAPLIQ general manager Steven Laperriere, fearing it could lead to abuses.

- 'Long process' of reflection -

"Nobody just gets up one morning and says, 'I'm going to ask for medical assistance in dying today,'" underscores Georges L'Esperance, a retired neurosurgeon who has helped many patients access MAID.

"It's a long process" of reflection, he says.

Doctors play a central role in MAID, with two of them required to consider and approve each request.

L'Esperance says he makes sure to be "always very close to the patient" so that he or she "feels a comforting presence" when the injections to induce a coma and then to stop their heart and breathing are administered.

Sandra Demontigny, who suffers from early Alzheimer's, has campaigned for years for the right to file advance MAID requests.

However, she will have to wait as the new rules on advance requests will not take effect for another two years, in order to give physicians and institutions time to set up proper protocols.

The former midwife worries about finding herself in the late stages of the disease "a prisoner in my own body."

The 44-year-old recalled her father in the late stages of the incurable disease having "almost no more autonomy." He died at the age of 53.

"For me, there's no added value in going through this and I don't want my loved ones to go through it either," she said.