A genetically-modified pig kidney is continuing to function well a record-breaking 32 days after it was transplanted into a brain dead patient, a medical center said Wednesday.

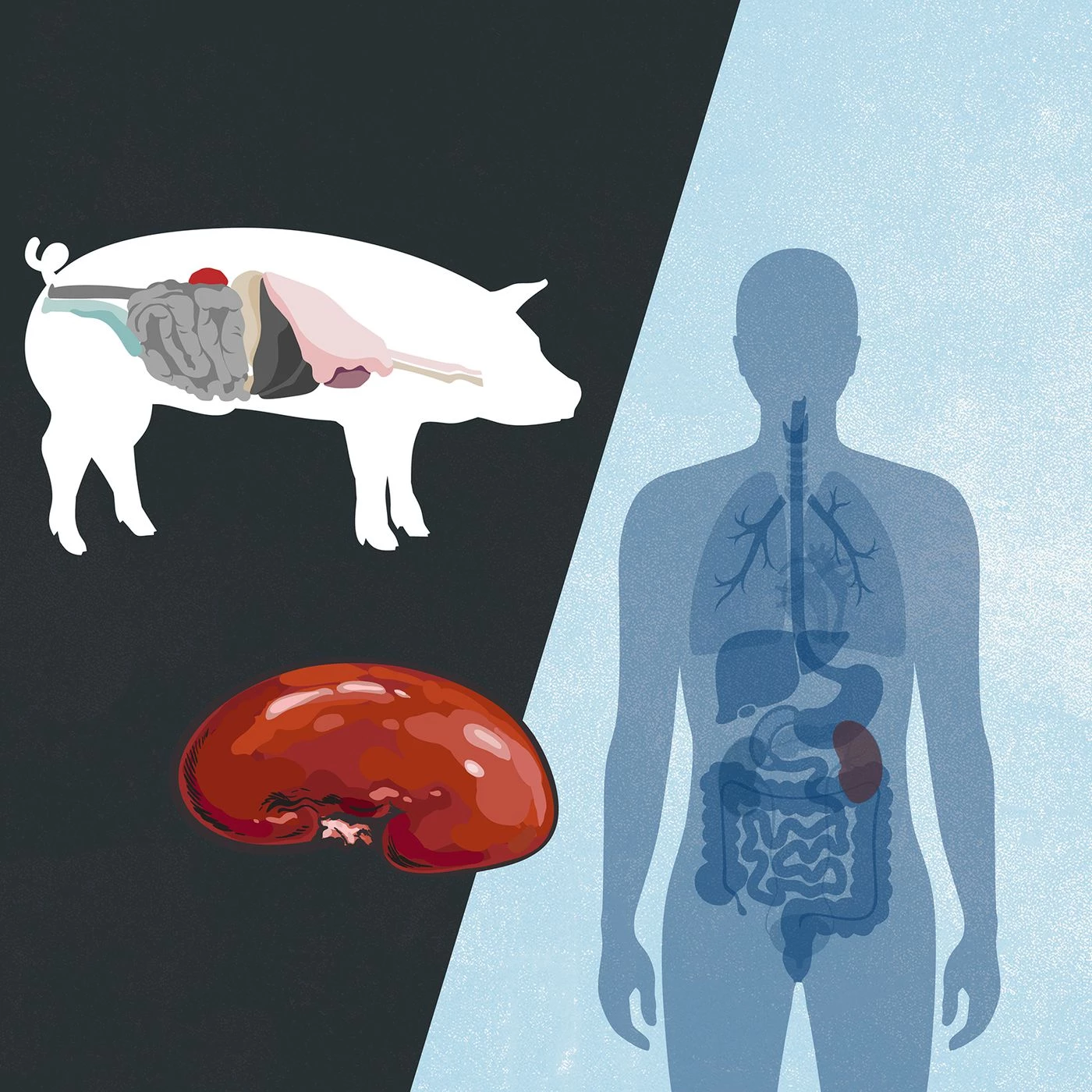

The experimental procedure is part of a growing field of research aimed at advancing cross-species organ donation and thus reducing transplant waiting lists.

There are more than 103,000 people waiting for transplants in the United States, 88,000 of whom need kidneys.

"This work demonstrates a pig kidney -— with only one genetic modification and without experimental medications or devices -- can replace the function of a human kidney for at least 32 days without being rejected," said surgeon Robert Montgomery, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

Montgomery carried out the first genetically modified pig kidney transplant to a human in September 2021, followed by a similar procedure in November 2021. There have since been a handful of other cases.

While previous such transplants have involved up to 10 modifications, the latest experiment involved just one: the gene involved in the so-called "hyperacute rejection," which would otherwise occur within minutes of an animal organ being connected to a human circulatory system.

By "knocking out" the gene responsible for a biomolecule called alpha-gal -- which otherwise would be a prime target for human antibodies -- the NYU Langone team were able to stop immediate rejection.

"We've now gathered more evidence to show that, at least in kidneys, just eliminating the gene that triggers a hyperacute rejection may be enough along with clinically approved immunosuppressive drugs to successfully manage the transplant in a human for optimal performance—potentially in the long-term," said Montgomery.

They also embedded the pig's thymus gland -- responsible for educating the immune system -- in the kidney's outer layer, in order to prevent a more delayed host rejection.

Both of the patient's own kidneys were removed, then one pig kidney was transplanted, and started immediately producing urine.

Monitoring showed that levels of creatinine, a waste product, were at optimal levels, and there was no evidence of rejection.

Crucially, no evidence of porcine cytomegalovirus -- which may trigger organ failure -- have been detected, and the team plan to continue monitoring for another month.

The research was made possible by the family of the 57-year-old male patient who had elected to make his body available for science.

In January 2022, surgeons at the University of Maryland Medical School carried out the world's first pig-to-human transplant on a living patient. He died two months after the milestone, with the presence of porcine cytomegalovirus in the organ later blamed for his death.