Female genital mutilation: entrenched ritual with devastating effects

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

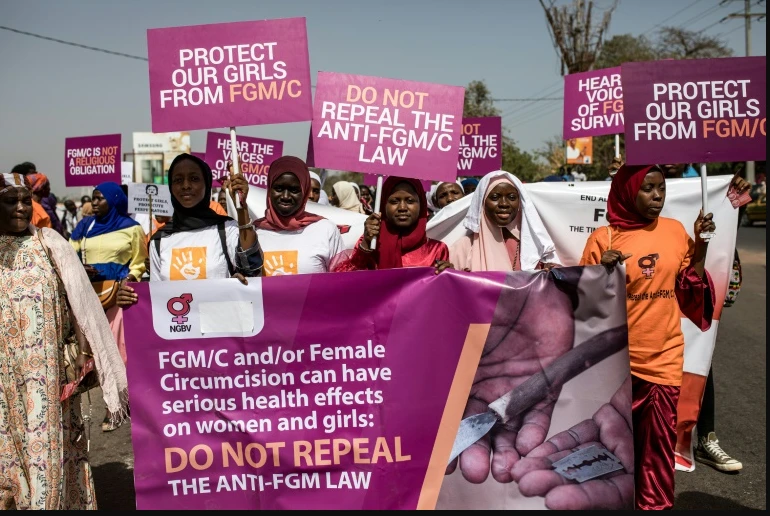

Lawmakers in the West African nation of The Gambia have rejected a highly controversial push to try to overturn a ban on female genital mutilation.

Gambia 2015 banned the ritual forced on millions of girls in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, but it remains widespread.

Here are some key facts about an ancient practice that is based on a range of ideas about female sexual purity, hygiene, social acceptance, and male sexual pleasure.

Vicious display of male power

The term female genital mutilation (FGM) covers all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons, according to the World Health Organization.

It can involve the partial or total removal of the external and visible part of the clitoris, or of the clitoral glands and the inner folds of the vulva.

In its most extreme form, the ritual can involve infibulation, the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal, leaving just a tiny orifice for urination and menstrual flow.

How the ritual is practiced differs from country to country.

Apart from causing severe pain, it can cause potentially deadly health complications, from infections and bleeding to infertility and complications in childbirth.

It also impairs female sexual pleasure.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres 2023 described it as "one of the most vicious manifestations of the patriarchy that permeates our world".

Number of victims growing

Despite a growing global push to ban a practice widely seen as abhorrent, the number of victims of female genital mutilation has grown by 15 percent since 2016 to an estimated 230 million, according to the UN Children's Fund UNICEF.

UNICEF has blamed the increase on population growth in the countries where FGM is practiced.

The ritual is most widespread in Africa, where more than 144 million women and girls have been mutilated, mainly in the Horn of Africa.

In Somalia, 99 percent of females between 15 and 49 have been mutilated, 95 percent in Guinea, 90 percent in Djibouti, and 87 percent in Egypt, according to UNICEF.

UNICEF estimated a further 80 million victims in Asia (Indonesia and the Maldives) and six million in the Middle East (Yemen and Iraq).

Education the key

While the number of victims remains staggering, the practice has sharply declined in some countries.

In the West African nation of Burkina Faso, the proportion of girls aged 15-19 to have undergone FGM has fallen from 83 percent to 32 percent in the past 30 years.

In Liberia, which elected Africa's first woman leader in 2006, the proportion has fallen from 54 percent to 20 percent.

"It's clear that this generation of girls is less exposed to female sexual mutilation than their mothers," Isabelle Gillette-Faye, the president of a French association that campaigns against the practice, told AFP, calling the declines in some countries "very encouraging".

The UN has set itself a goal of eradicating FGM by 2030.

To achieve that, improvements will need to come 27 times more quickly to compensate for demographic growth in the countries concerned, according to UNICEF.

Beyond legislating to ban the practice, Gillette-Faye argues that improving access to education for girls and boys alike is key to changing attitudes.

"In every country, without exception where the level of schooling reaches the end of primary school there is a significant drop," she said.