First Liberia crimes against humanity trial opens in France

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

France's first trial of a participant in Liberia's bloody civil wars began on Monday, with former rebel commander Kunti Kamara facing charges of crimes against humanity, including torture.

The allegations before the Paris criminal court against Kamara, 47, date back to 1993 and 1994, early years in the back-to-back conflicts that would ultimately kill 250,000 people between 1989 and 2003.

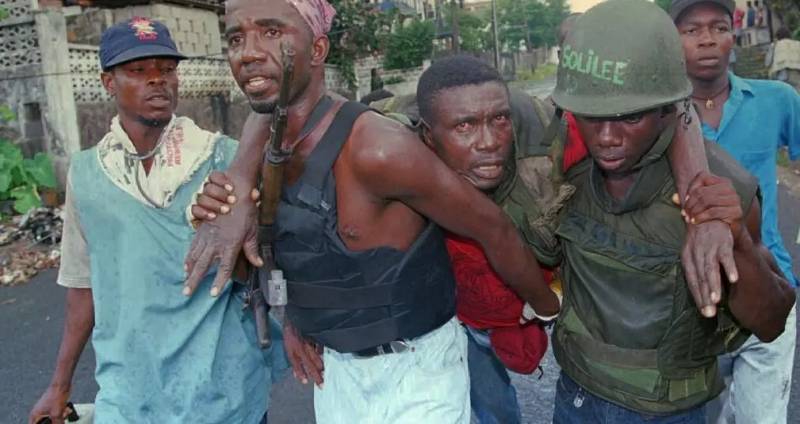

The conflicts were marked by mass murders, rape and mutilations, in many cases by child soldiers conscripted by warlords.

Atrocities against civilians were common, with drugged fighters chopping off people's limbs.

A truth and reconciliation commission was set up in 2006 to probe crimes committed during the war, but its recommendations, published in 2009, have remained largely unimplemented in the name of keeping the peace.

And many warlords who were incriminated are still considered heroes in their communities.

"Liberia is a country where total impunity for these crimes still prevails," said Sabrina Delattre, a lawyer representing several Liberians and the Civitas Maxima aid group, which is also a plaintiff in the case.

- Killing, rape and looting -

Kamara was a regional commander of the United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy (ULIMO), a rebel group that fought the National Patriotic Front of ex-president Charles Taylor.

According to investigators, he headed an ULIMO faction in Lofa county, a strategic area in northwest Liberia.

As well as torture, he is also accused of involvement in "mass and systematic practices of inhumane acts... for both political and ethnic motives", including killing, gang rape and looting.

Kamara, shaven headed and with a black moustache, spoke to confirm his name to the court, where he faces a maximum possible sentence of life in prison.

In a statement, prosecutors laid out graphic details of Kamara's alleged methods, including killing a whistle-blower with an axe before eating his heart.

The charge sheet also alleges that young women were raped and kept as sex slaves under Kamara's authority.

Kamara, who was arrested near Paris in September 2018, denies the charges.

"He has acknowledged that he was an ULIMO soldier but has always denied committing atrocities against civilians," his lawyer Marlyne Secci said.

Kamara is "approaching this court case as someone who will be tried in a country that is not his own," she added.

The case was brought by the crimes against humanity division of the Paris court, which was set up in 2012 to try suspected perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide detained on French soil, irrespective of where their alleged crimes were committed.

Set to last until November 4, this is the first case taken by the unit that is not related to the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

"This trial is a significant step for justice for victims of atrocities committed in Liberia's first civil war," said Benedicte Jeannerod, director of Human Rights Watch in France.

But she added that further reforms were needed to allow French proceedings for more victims of foreign atrocities.

- Rare convictions -

So far only a handful of people have been convicted in Liberia itself for their part in the conflict, and efforts to establish a war crimes court in the country have stalled.

Former Liberian warlord-turned-president Taylor was imprisoned in 2012, but for war crimes committed in neighbouring Sierra Leone, not in his own country, where he also rampaged.

Other former participants in the Liberian wars have been tried abroad in recent years.

In Finland, suspected warlord Gibril Massaquoi was acquitted in April over alleged crimes in the later years of the second war.

A Swiss court last year sentenced former ULIMO leader Alieu Kosiah to 20 years in prison for war crimes.

And in the United States, the former warlord Mohammed Jabateh was jailed for 30 years in 2018 -- albeit for lying on his asylum application rather than for his alleged crimes.

"The victims are still very traumatised and need this justice, but they fear pressure from former rebels who still have powerful networks in Liberia," Delattre said.