UN sets sail for battle with 'biopirates'

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

The appropriation of traditional knowledge surrounding genetic resources is in the crosshairs at the United Nations, with a fortnight of talks opening Monday on putting an end to so-called biopiracy.

After more than 20 years of negotiations, the UN's World Intellectual Property Organization hopes to conclude a treaty that will protect such knowledge from exploitation by enforcing greater transparency in the patenting system.

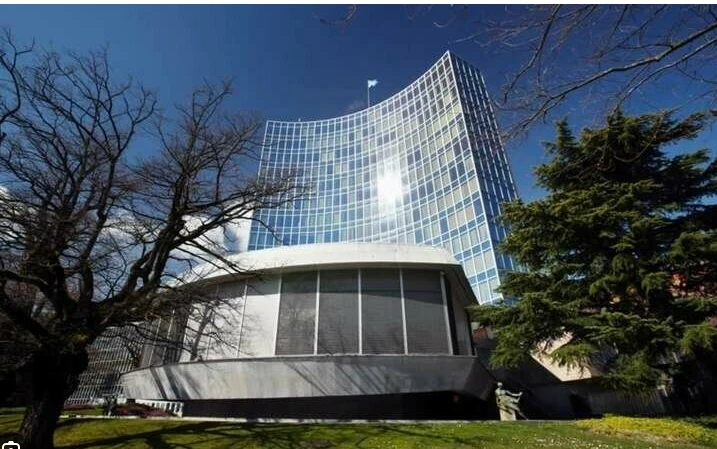

"This is a historic moment," said WIPO chief Daren Tang, as the agency's more than 190 member states gather at its Geneva headquarters for talks that run until May 24.

"It's about fighting biopiracy, that's to say the use of traditional knowledge or genetic resources without the agreement of those who held them and without them being able to benefit from them," said Christophe Bigot, who is leading the French delegation.

While natural genetic resources -- such as those found in medicinal plants, agricultural crops and animal breeds -- cannot be directly protected as international property, inventions developed using them can be patented.

These resources are increasingly used by companies in everything from cosmetics to seeds, medicines, biotechnology and food supplements.

Non-governmental organisations cite the cases of maca plants from Peru, hoodia from South Africa and neem from India.

- Search for consensus -

Although arduous, there have been victories, as with neem. In 1995, the properties of this tree -- used in India for thousands of years in agriculture, medicine and cosmetics -- were the subject of a series of patents filed in particular by the US chemicals giant W. R. Grace.

After 10 years of fighting, the European Patent Office withdrew a patent for the first time on the grounds of "biopiracy".

The draft WIPO treaty stipulates that patent applicants will be required to disclose which country the genetic resources in an invention came from, and the indigenous people who provided the associated traditional knowledge.

Opponents of the treaty fear it will hamper innovation.

But proponents say an additional disclosure requirement would increase legal certainty, transparency and efficiency in the patent system.

They say it will "help ensure that such knowledge and resources are used with the permission of the countries and/or communities from which they originate, enabling them to benefit in some way from the resulting inventions", according to Wend Wendland, the director of WIPO's traditional knowledge division.

Wendland said adoption of the instrument "would conclude over two decades of negotiations on a matter of great significance for many countries".

WIPO hopes countries can find a consensus.

Disagreements persist, notably on setting up sanctions, and the conditions for revoking patents.

"The text has been narrowed down a lot in order to arrive at some potential compromise," expert Viviana Munoz Tellez of the South Centre, an intergovernmental think-tank representing the interests of 55 developing countries, told AFP.

- Overcoming North-South clashes -

The proposed treaty has "symbolic value because it's the first time that there will be some reference for example to traditional knowledge in an IP instrument", said Munoz Tellez.

It will have a direct effect in terms of transparency, even if it does not resolve every problem, she said.

More than 30 countries have such disclosure requirements in their national laws. Most of these are emerging economies, including China, Brazil, India and South Africa, but there are also European states, such as France, Germany and Switzerland.

However, these procedures vary and are not always mandatory.

"It is important to get beyond clashes that are too sterile" between the global North and South, said one diplomat, on condition of anonymity.

"Several countries in the North have genetic resources, like Australia or France, and several countries in the South have very large laboratories and companies that use genetic resources, like India or Brazil," the source added.

Two years ago, countries unexpectedly agreed to convene a diplomatic conference in 2024 to conclude an agreement.

Only the United States and Japan officially dissociated themselves from the decision, without however opposing the consensus.

Japan's mission in Geneva told AFP it hoped the outcome of the conference would be "clear, reasonable and practical to apply".