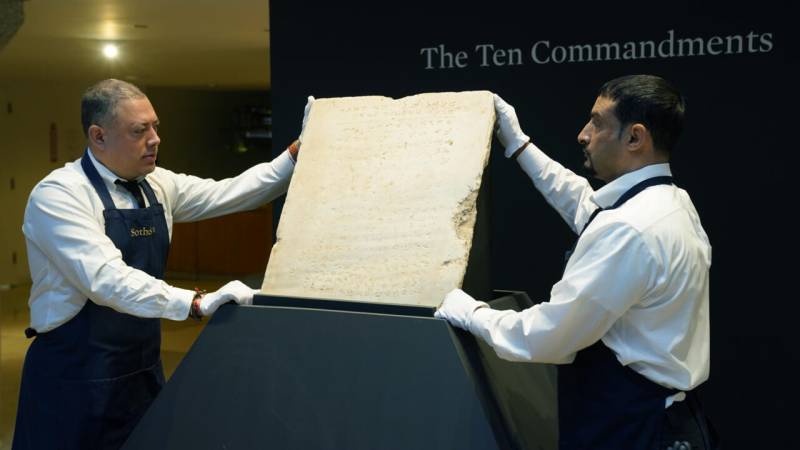

Stone tablet engraved with Ten Commandments sells for $5 million

Stay tuned with 24 News HD Android App

A stone tablet carrying engravings of the Ten Commandments sold for $5 million at auction on Wednesday, Sotheby's announced.

The high figure was notched despite questions around the tablet's authenticity: no one has claimed it is the original, of Biblical fame, but some experts expressed doubts around its purported provenance, dating between the years 300 and 800 CE.

Another ding against the 115-pound (52-kilogram) slab, said to be discovered in 1913 in what is now Israel, is that it only contains nine of the 10 commandments considered holy by both Jews and Christians.

Excitement around it prevailed, however, as bids eventually raced up to $4.2 million, with the final sale coming in at $5 million including fees.

Those shocked at the price can swear freely: the tablet doesn't contain the commandment against taking the Lord's name in vain.

The New York auction house had expected it to sell for $1-2 million.

The tablet was said to be discovered during excavations for the construction of a rail line.

It carries a Paleo-Hebrew script, and, according to Sotheby's, was held privately until an archeologist living in Israel realized its importance and purchased it.

"It's been thrilling to work with this object of antiquity. There is no other stone like it in private hands," Sharon Liberman Mintz, a specialist on Jewish texts for Sotheby's, told AFP.

The slab eventually made its way to the Living Torah Museum in Brooklyn before being sold to a private collector.

In a statement, Sotheby's said that the tablet has been studied "by leading scholars in the field and published in numerous scholarly articles and books."

However, multiple experts told the New York Times they had questions about its origins.

"Maybe its absolutely authentic," said Brian Daniels, of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center in Philadelphia, though he cautioned: "Objects from this region of the world are rife with fakes."

"There is no way" the age of the inscription can be known, Christopher Rollston, a professor of Biblical and near eastern languages and civilizations at George Washington University, told the paper.

"We have zero documentation from 1913, and since pillagers and forgers often concoct such stories to give an inscription an aura of authenticity, this story could actually just be a tall tale told by a forger or some antiquities dealer."